|

6.

The great colonization

During the High Middle Ages

the peripheral areas of the Bohemian Massif extended as far as

a day's footmarch and were covered with forests which were

almost impenetrable. Only a few footpaths and wagon trails

crossed it such as the old-famous "Golden Steig"

from Passau through the valley of the Ilz or the trail from

Silesia at Liebau to Nachod. These routes did not only carry

the trade with a multitude of goods, they also brought

settlers into the forest and mountain areas. Their harbingers

were the clergymen, traders, princesses, noblemen and monks

whom the Bohemian court had invited into the land. The German

colonization unfolded with enormous impact around the middle

of the 13th century. It progressed in three parallel streams

of crafts, husbandry and mining. Most often a "Lokator"

was hired by the sovereign to settle colonizers on a

designated piece of land. . His organisational endeavors

usually were awarded with the hereditary title of magistrate

and a guesthouse license as a commission. The newly founded

towns and localities were subject to the legal systems of the

towns and villages from where the settlers came. The

development and administration of German towns became a model

for the construction of the Bohemian towns. King Ottokar II

evidently saw the German colonization as a means of scaling

down the nobility and for increasing his financial and

political power. In addition, towns made bids on their own for

colonists and established villages to fill their need for an

agrarian back country. This led nearly everywhere to the

emergence of groups of towns and villages entailing a rapid

growth of the German-speaking population.

Immigration from various

regions of the Empire is the source for the various

Sudetengerman dialects and to some extend for the differing

architectural styles as well. The names of villages provide

distinct evidence of older Slavic origins (-itz) or of younger

ones related to colonization (-dorf, -berg, -wald). Newly

founded German settlements were usually named by the locator

or the settlers chose a name related to the landscape, whereas

the Slavic public retained an old castle or field name. This

explains that the later introduced official bilingualism often

led to German and Czech place names the meanings of which do

not reveal a relation.

Northern Bohemia was settled

mostly by Lausitzers whose dialect with a rolling

"R" remained a distinctive mark over centuries. Many

monasteries and monastic orders took part in the colonization.

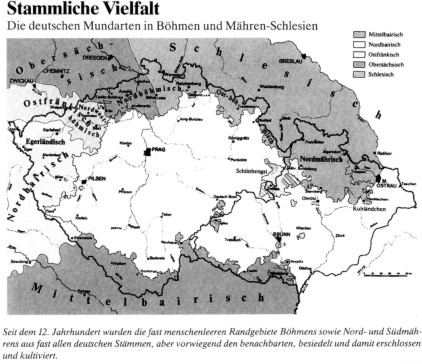

Ancestral

Diversity

The German dialects in Bohemia

and Moravia-Silesia |

|

|

| The

practically unpopulated peripheral areas of Bohemia

as well as South- and North-Moravia were settled,

developed and cultivated by settlers since the 12th

century from almost all German regions, but

predominantly from adjacent ones. |

The German

colonization, the

founding of cities, the development of mining for silver and

a wealth of other minerals made the kingdom of Bohemia

indisputably the empire's most important duchy which

expanded its influence from the Baltic to the Adriatic Sea.

Who would know that Königsberg, East Prussia, was founded

by Ottokar II and that his name is embodied in Ottakring, a

suburb of Vienna. Undeniably, the Bohemian kingdom also

benefited from the weakness of the empire during the "dreadful

interregnum" (1256-1273). At the peak of his power,

Ottokar II saw his plans thwarted by the election of Rudolf

von Habsburg as German king. In a fight for power, he was

defeated and lost his life (battle of Marchfeld). His son

and grandson were not predestinated to good fortune. With

them the male lineage of the Przemyslids died

out and unruly times followed. Nearly anarchic conditions

arose under Heinrich von Kärnten. Nobility and burghers

fought each other and moved the king back and forth like a

chess board figure. The burghers of the cities demanded a

voice in the Landtag, the nobility refused. This was the

first national conflict in Bohemia, for the burghers were

Germans, the nobility mostly Czech.

|